This post is reproduced with permission from C. M. Naim. http://cmnaim.com/2016/08/indias-national-library-goes-digital-sort-of/

C.M.Naim, among other things, is an Urdu scholar and translator of the Urdu poet Mir Taqi Mir’s Zikr-i-Mir, Professor Emeritus of South Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Chicago

In April 2014, The Guardian published a longish piece by Samuel Gibbs entitled, “The most powerful Indian technologists in Silicon Valley.” It opened: “Ever since waves of Indian graduates poured into Silicon Valley in Northern California in the 1970s and 1980s, talented Indians have made breakthroughs, pushed boundaries and held positions of power in the world of technology and media.” Gibbs then went on to give brief but substantial accounts of the achievements of eleven such Indians, nine men and two women. Included were such luminaries as Ajay Bhatt—“credited as being the father of the USB standard”—and Vinod Dham—“The father of the famous Intel Pentium processor.” What is also striking about these men and women is the fact that almost all of them received their foundational education in India, in some of its most prestigious institutions. One may then rightly assume that those institutions, and others like them, must have by now produced a very large number of well-trained and talented people. Too numerous, perhaps, even to imagine. So why is it that not one of them apparently found his or her way to be on the staff of the National Library at Kolkota? For as anyone who visited it knows that the National Library’s website is nothing short of a disgrace to such a prestigious institution.

In April 2014, The Guardian published a longish piece by Samuel Gibbs entitled, “The most powerful Indian technologists in Silicon Valley.” It opened: “Ever since waves of Indian graduates poured into Silicon Valley in Northern California in the 1970s and 1980s, talented Indians have made breakthroughs, pushed boundaries and held positions of power in the world of technology and media.” Gibbs then went on to give brief but substantial accounts of the achievements of eleven such Indians, nine men and two women. Included were such luminaries as Ajay Bhatt—“credited as being the father of the USB standard”—and Vinod Dham—“The father of the famous Intel Pentium processor.” What is also striking about these men and women is the fact that almost all of them received their foundational education in India, in some of its most prestigious institutions. One may then rightly assume that those institutions, and others like them, must have by now produced a very large number of well-trained and talented people. Too numerous, perhaps, even to imagine. So why is it that not one of them apparently found his or her way to be on the staff of the National Library at Kolkata? For as anyone who visited it knows that the National Library’s website is nothing short of a disgrace to such a prestigious institution.

Click on the above link and you will see the following:

Note the invitation—“User can register from this website free of cost”— on the left, spilling out of its box. Ignore the amateurish effect, and instead try to register. You will be immediately forced to make an arbitrary choice. There is on the right of the screen a tempting box titled “New User?” with a winking sign saying “Register Now!” But there is also smack in the middle of the screen a box marked “User registration.” Most likely, you will do what I did and click on the “New User” box, to be greeted only with the following bracing message: “This facility will be made available soon.” Now try the box in the middle. It works. You can register – but only if you are an Indian citizen. It does not say that in so many words. However, I as an American citizen was in no position to answer all the “mandatory” questions, even if I chose to ignore their highly obtrusive nature. I gave up and consoled myself by concluding that “User Registration” was perhaps not meant for those who only wished to use the website and the NL’s online information resources.

I next tried the button saying “View Recently Digital Books” (sic), assuming that they actually meant “Recently Digitized.” What did I find? Just one title, as can be seen below.

Ignore your disappointment, ignore the incongruity of “1 Records Found.” But do consider the details of the one “recently digital” book. The author is given as “Ober, Fredwick Alboin.” His parents, however, had named him: Fredrick Albion Ober. Now look at the title of the book as offered by the National Library of India: “Comps in Carbbees; the adventures of a naturalists in the Lesser Antilles.” The book when it came out in 1880 was actually titled: “Camps in the Caribbees: the adventures of a naturalist in the Lesser Antilles.” Four serious typos in a context where not one should have happened.

I next tried the box in the middle of the page titled, “Digitised Book (sic),” expecting to find some description of the nature and number of the books, with perhaps an alphabetical list of the most prominent authors so far included. Instead I found I had to blindly try, and if I were lucky I could find something. As fate would have it, almost all the times I was only told: “No records found.” It soon became obvious that no browsing was possible. One could only make a specific request and then pray for good luck.

Finally, I decided to search the library’s online catalog as offered on the home page. My recent research interest has been popular fiction in Urdu at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20 centuries, in particular what was translated from the English. Two authors, George W.M. Reynolds and Marie Corelli, had been particular favorites in Urdu, as in fact they had been in several other Indian languages. I thought the National Library should have a good record of the titles by these authors that had been available in India as well as the translations that appeared in Indian languages. I was not disappointed. A substantial number of the two authors’ early editions are preserved. I also found titles of some translations in Bengali and Malayalam. But very few. Far fewer than were actually done in those two languages. And no mention of any translation in Urdu, though at least 34 novels of Reynolds and 5 of Corelli were to my knowledge translated and avidly read in Urdu in the 1920s.

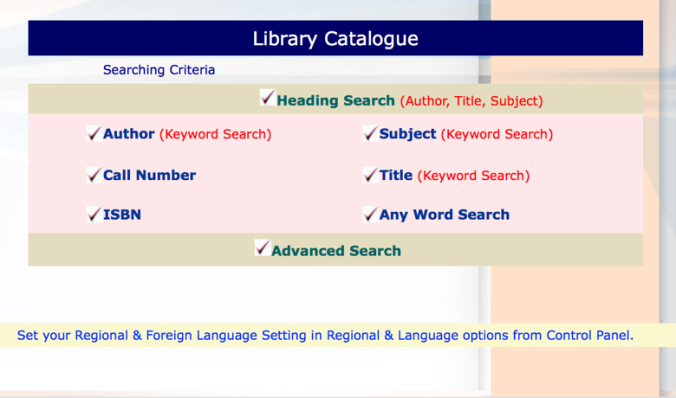

I also found that there was no easy way for me to check Urdu titles. As shown below, the page invites readers to use regional languages but where is the “Control Panel” that it asks them to use?

I had to resort to Romanized forms of Urdu words. It worked – mostly. But it would have more helped if they had offered a guide to their Romanizations. It turns out that there is no fixed system. Different people on the staff have differently Romanized Urdu titles and authors’ names. I wonder if that has happened with other languages too or was that some special treatment meted out to Urdu? Surely, it is not fair to change Urdu ‘z’ to Hindi ‘j’ even in Romanization. Not in Kolkota, where people lustily pronounce ‘z’ and ‘f’ even where they are not required to.

Why should this be the case? A friend suggested the practice of “tendering out” such jobs could be to blame. The library wished to have a website; it asked for tenders from different IT firms; then chose the least costly, hence the least efficient. The usual bureaucratic fiasco. There is also that attitude so prevalent among Indian librarians. Very few of them think of themselves as providers of an essential service to the general public. Most of them view themselves simply as custodians of the contents of their institutions—contents that they preserve and protect but do not, in the same measure, also make available to rightful users. After visiting the National Library’s website it was obvious to me that no one had bothered to try it out and see if it actually worked. They can now claim, like everyone else, to have a website, that it worked or not was of little importance.