Deepak Naorem

A stray reference or scribbling on the margins of a document in an archive can lead to the discovery of an entirely unknown archive and recovering of neglected histories. Many historians experience such discoveries in their careers.

In 2011, I started working on the history of the Second World War in Northeast India and it took me to the National Archives of India to study the Indian National Army papers (Private paper collections, NAI, 1942-46).

This private paper is indeed a significant source for writing the history of the INA, their actions in Burma, Manipur and the former Naga Hills, and the participation of the locals in the war either on the side of the Allied forces or INA/Japanese forces.

A reference in a Ministry of State (Political Branch) document, dated 1949, to war compensation in Manipur and the Naga Hills for losses incurred in connection with Allied action during the war, however, caught my attention and put me on a research trajectory quite removed from what I originally planned.

Further digging in the National Archives led me to a series of correspondences between the Assam Government and the Ministry of Defence, which constantly referred to nearly a hundred thousand petitions from Manipur and the Naga Hills, seeking monetary compensation from the state for losses and damages during the war.

This revelation made me anticipate the possibility of locating these petitions in some dust-covered boxes in dark and damp record rooms of provincial archives of the region, and inspired my visits to the record rooms of District Collector’s offices and State Archives in Assam, Manipur and Nagaland.

My encounters with these archives led to the beginning of a long process of unlearning and relearning about the complexities of local archives which were created in the frontier of the British Empire, and are now located in the borderlands of a state-nation.

For months, I looked for these petitions in the State Archives without any success.

None of the local historians I consulted had encountered or heard of these petitions. Their presence in the archives is also not indicated by the inadequate catalogues and cataloguing systems used in these local archives.

After much socializing with the staff of the State Archives in Imphal, and sharing my disappointment with them over cups of tea served in the quintessential glass cups, they informed me that the archives also store a large volume of documents which remained unarchived and uncatalogued.

It was in these categories of files that I made my subsequent discovery.

A large volume of files from various state departments, district collector offices, the old secretariat library and private custodians had been transferred to the State Archives since its establishment in 1982. Such transfer to the archives does not necessarily mean that they will be made accessible to the historians and public.

In fact, a large number of such documents, which are on the archive premises remain unarchived, and a significant number remained uncatalogued.

Here I am reminded of Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s work Silencing the Past, where he argues that the roots of silencing in history are structural, and begin even before the birth of the historian. Silencing happens at many crucial moments, and one of them is ‘the moment of fact assembly’ or the making/constitution of the archive.

Documents and manuscripts remain stuck in transit between the departments and donors who transferred the files and manuscripts and the shelves or dark storerooms in the archive building.

Since they are either unarchived or uncatalogued, they remained inaccessible to historians and this significantly contributed to the silencing of various histories. The silencing is exacerbated when files are disposed of by burning and disposing of volumes before they could be transferred to any kind of archive.

Monetary compensation and the Claim office

Before the end of the war itself, thousands of people from Manipur state and the Naga Hills started writing petitions seeking monetary compensation from the state. This led to the creation of the Claim office in Shillong and later with branches in Imphal and Kohima, a separate office to deal with this large number of petitions.

In Manipur, the files of the Claim Office along with these petitions were transferred to the State Archives (date of transfer unknown). These files have been given row and shelf numbers, indicating that they were archived. However, these files have not entered the pages of the catalogues of the archive.

Writing a vernacular history of the war

As a result, scholars are not aware of the existence of these files and petitions, and they cannot be requisitioned. Histories of the Second World War in the region are dominated by imperial and national histories. Oral accounts have been used by historians recently to recover vernacular histories of the war. However, these thousands of petitions in a state of transit in the archives of the region provide an alternative and quite an extensive source for writing a vernacular history of the war and help in recovering certain histories of the war which remain silenced.

Negotiating state and bureaucracy

Writing petitions emerged as a popular strategy for negotiating the colonial state and the bureaucracy in the everyday lives of people in the region since the early twentieth century. The local archives are hence full of different types of petitions. Seeking monetary compensation from the states is also not new in the region.

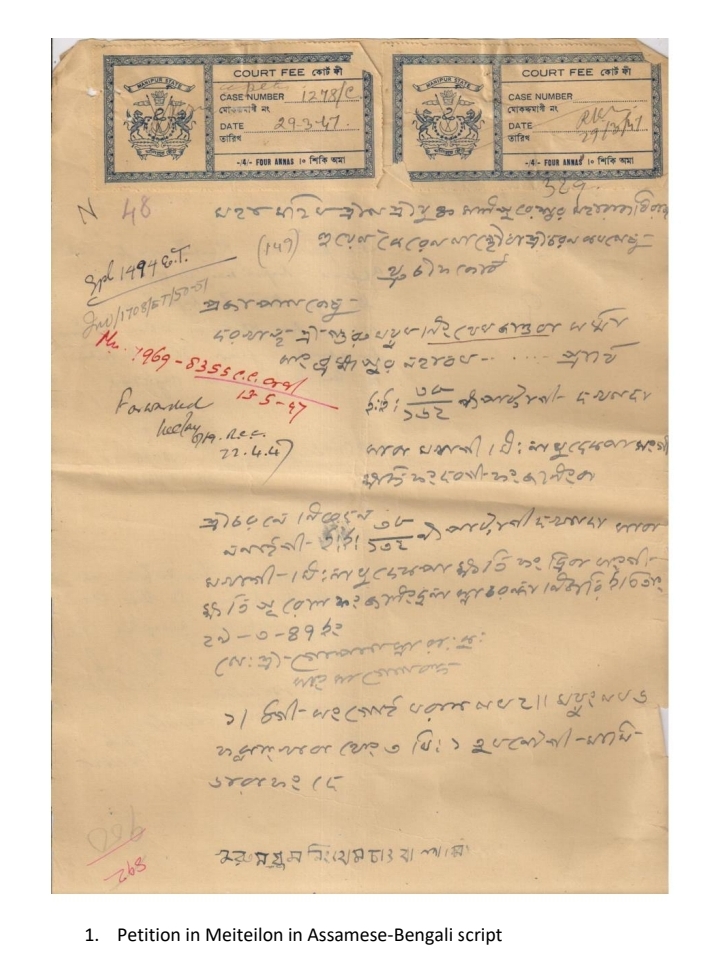

Thousands of individuals and villages in Manipur and the Naga Hills wrote petitions seeking compensation, monetary and in-kind, from the state. These petitions were either written by individuals or by a class of professional petition writers who wrote these petitions for a small remuneration. They were written in English or Meeteilon (Manipuri) in either Roman or Eastern Nagari script.

These petitions (some of them lengthy), are testimonies of their experience of the war and narrated their experience of displacement, deaths, bombing, destructions and loss of their movable and immovable properties, hunger, an outbreak of diseases, intimacies, encounters with the Allied and the Japanese armies and the failed relief and rehabilitation works of the state.

According to the Chief Claim officer in Shillong, a total number of 107747 and roughly 18000 petitions were received from Manipur state and the Naga Hills respectively, and they offer an alternative non-national and non-imperial history of the war.

The bureaucratic responses of the successive states in the region to these petitions also tell us about the complicated process of decolonisation and the transfer of power in the region. In the former Manipur state, the wartime colonial administration invited petitions from the distressed population. After 1947, the Manipuri administration started the process of assessing the petitions and distributing monetary compensation to some of the petitioners.

Once the Indian state took over the administration of the region in 1949, it introduced changes in the process of assessing compensation, which included introducing a form called ‘Form A for Claim Petition’ to replace the older lengthy unmanageable petitions.

To process their compensation claims, the petitioners needed to fill up this form. The purpose of this form was to isolate the information which was crucial for handling the dire issue of war compensation from the existing lengthy petitions. These large number of petitions and the subsequent bureaucratic writings and documentations as a response to these petitions, which are mostly in a state of transit in the archives of the region, are indeed exciting sources for not only recovering vernacular histories of the Second World War in Northeast India, but also an unconventional political history of the region.

DEEPAK NAOREM is Assistant Professor at Daulat Ram College, University of Delhi. His research interests include the history of colonial Northeast India and the Trans-Himalayan Region, history of literary cultures and of the Second World War in SOUTHEAST Asia.

Some of his publications are ‘Japanese invasion, war preparation, relief, rehabilitation, compensation and ‘state-making’ in an imperial frontier (1939–1955)’ in Asian Ethnicity, ‘A Contested Line- Implementation of Inner Line Permit in Manipur’, in Kafila on September 15, 2015, ‘Myth Making and imagining a Brahmanical Manipur since 18th century CE’, and ‘Remembering Japan Laan: Struggle for Relief, Rehabilitation and Compensation’, in NE Scholar Journal (July 2018)